UK Onshore #2: The Midland Valley of Scotland

- Ollie Button

- Aug 10, 2021

- 4 min read

This blog series is an extended version of my published article by Geo Expro (Vol. 18, No.3, p60), which can be accessed by clicking the button below:

Introduction: The Central Belt

Past, present, and future industry is continually drawn to the Midland Valley of Scotland. With the welcomed energy transition in full swing, should we continue conventional exploration for oil and gas in the Central Belt, where most of Scotland's population is based?

This 80km-wide, 420 million-year-old province contains thick accumulations of organic-rich rocks that played an instrumental role in the development of the world’s first oil industry.

For the second of my UK Onshore blog series, I dive into the rich history of Midland Valley of Scotland - home of the oil industry. I also review recent activity in the province and discuss a possible future outlook.

19th Century: Sparking an Industrial Revolution

Petroleum exploration in the Midland Valley of Scotland can be traced back to the 19th century. In 1851, wide seams of organic-rich shales were discovered in West Lothian, south of Firth of Forth.

James Young, an innovative chemist from Glasgow, experimented on how we could extract oil from lagoonal, ‘coaly’ oil-shale - otherwise known as Torbanite.

Torbanite helped fire up the start of the Industrial Revolution and awakened Scotland to the prospect of onshore oil.

Once many of the short-lived coal mines had been fully exploited, the industry transitioned to the ‘Lower Oil Shale Group’, with a better organic quality. The product of Young’s Enterprise was primarily used for lubricants and improved lamp oil - where 500,000 barrels of oil were produced at West Calder alone (DECC, 2013).

1900 - 1950: Battling the Demand of War

By 1913, there were up to 67 works distilling oil-shale in Scotland; Young’s Enterprise peaked at 2.1 million barrels of oil in total (DECC, 2013).

Although significant, it was only a fraction of the UK’s demand of ~50,000 barrels per day (UKOOG, 2013).

At the onset of World War I, demand for oil doubled. Surprisingly, however, domestic production halved. This was a result of cheap imports from the USA and the Middle East.

In 1934, Britain's oil and gas reserves were nationalised. George Martin Lees, head of exploration for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (former BP), recommended a licensing round under geological reasoning.

Lees noted conventional hydrocarbons within early-Carboniferous sandstones of the Cousland Anticline, south-east of Edinburgh in 1937.

The Cousland gas field produced up to 330 million cubic feet of gas, whilst the nearby Midlothian oil field (operated by Esso) produced up to 31,000 barrels of crude oil (DECC 2013).

With aid of the East Midlands Province (See Onshore #3), shale mining and conventional production in the Midland Valley of Scotland fuelled the British Naval Fleet and sustained demand during World War II.

1950 - 2000: Onshore vs. Offshore

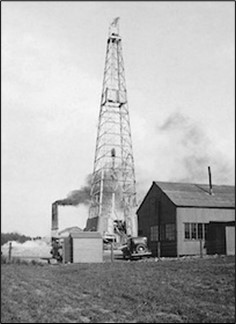

After the war, technological advances in seismic imagery revolutionised onshore activity. Deep-seated exploration and conventional production accounted for about 3000 barrels a day (UKOOG, 2013). Oil shale rapidly declined, whilst crude oil became the predominant source of energy.

The industry struggled to compete with cheap imports from the Middle East. Additionally, the UK Continental Shelf Act of 1964 popularised offshore operations in the North Sea. Thus, to the disappointment of many onshore workers, oil shale mining in the Midland Valley of Scotland was shut down.

The price of oil significantly rose in 1979, which led to the first official onshore licensing round in 1984. Burmah Exploration discovered oil at Milton of Balgonie, followed by a discovery of gas (~400,000cfd) at Bargeddie in 1989 (Marinex Exploration); unfortunately, both fields were deemed uneconomic.

Regulations were later revised into the UK Petroleum Act of 1998. At this time, however, the West Calder, Cousland, and Midlothian Fields were already abandoned.

21st Century: What's Next for the Midland Valley?

The Midland Valley of Scotland is a proven petroleum province. Despite this, most occurrences to date have been uneconomic and exploration wells have come to very little or no success.

In 2007, the Geological Survey concluded that prospects for coal bed methane would be a more likely target than conventional hydrocarbons. This is the current state for much of the Midland Valley of Scotland.

Between 2008 and 2011, however, Hurricane Energy conducted groundbreaking exploration on the previously overlooked Strathmore Basin. Regional satellite imagery and 2D seismic in the Perth-Crieff district revealed early signs of complex, fault-bounded structures that opened in conjunction with the Tay Graben - a possible trap structure for oil and gas.

Devonian outcrops indicate a series of mappable petroleum elements in the Devonian-aged Old Red Sandstone, as well as preserved Carboniferous fabric and trap integrity (i.e., not too starkly influenced by mountain-building events).

To the disappointment of an interesting commercial venture, the seismic survey was problematic. Local noise and concerns about damage to water mains resulted in a low-resolution profile. Although inconclusive, Hurricane stated: “The Strathmore basin does support a valid Devonian play”.

The Future: Not in My Backyard!

Whilst the Midland Valley is a proven petroleum province - commercial concerns come in respect for the community. The region is densely populated, and companies wanting to operate here will be challenged with NIMBY (“Not In My Back Yard”) opposition.

However, as evidenced by the covid-19 pandemic and severe winter storms such as ‘The Beast from the East', we are (unfortunately) highly dependent on imported resources to meet the UK’s demand for oil and gas.

With continued exploration for onshore resources in the UK, our reliance on imports could be reduced. Consequently, our economy may become self-sufficient and geopolitically safer.

170 years ago, the Midland Valley of Scotland ignited the industrial revolution. Today, it could help support a self-sustaining nation, and provide economic security for the green revolution.

References and Extra Reading

Please note that reference to photos and figures can be accessed by clicking the image.

Publicly available industry reports available in the UK Onshore Geophysical Library at: https://ukogl.org.uk/

DECC, 2014. “The Carboniferous Shales of the Midland Valley of Scotland: Geology and Resource Estimation”: https://www.ogauthority.co.uk/media/2765/bgs_decc_mvs_2014_main_report.pdf

DECC, 2014. “Unconventional Resources in Great Britain – Midland Valley of Scotland BGS Carboniferous Study”: https://www.ogauthority.co.uk/media/2767/mvs_media_summary.pdf

DECC, 2013. “The Hydrocarbon Prospectivity of Britain’s Onshore Basins”. Promote UK 2014: https://www.ogauthority.co.uk/media/1695/uk_onshore_2013.pdf

Kent, P.E., 1985. “UK Onshore Oil Exploration, 1930–1964”. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 2(1), pp.56-64.

Oil & Gas Authority (OGA). Exploration & Production: Onshore Reports and Data: https://www.ogauthority.co.uk/exploration-production/onshore/onshore-reports-and-data/

Suzanna Hinson, Nikki Sutherland, Sara Priestley, Paul Bolton and Lorna Booth. “Future of the UK Oil and Gas Industry”. House of Commons Library, Debate Pack.

UKOOG, 2013. “Onshore Oil and Gas in the UK”: https://www.igasplc.com/media/11155/ukoog-onshore-oil-and-gas-in-the-uk.pdf

Comments